Student supervision and feedback

Although students will be gaining basic knowledge during the academic course, a major aim of professional practice is for you to impart your more specialised knowledge and expertise. In addition to working alongside you and your colleagues during a professional practice placement, the process of supervision and receiving feedback provides a valuable opportunity for students to deepen and consolidate their learning, and to set new goals for themselves. The interaction between the student and you, as practice educator, is the subject of this section. Each profession will have a slightly different approach to "supervision" and "feedback" but it is important that you understand the need to facilitate the development of your student in a way that is appropriate within your setting and profession.

Giving feedback to students

Giving feedback to students in a way which enhances, rather than damages their self-esteem, is an important skill that is seldom taught (Rogers 2001). Evidence shows feedback should:

-

be prompt, following the event

be prompt, following the event - contain encouragement

- be specific about why something was good or not up to standard, indicating what the student can do about it

- not focus on too many different aspects at the same time

- be unambiguous and clear.

There is a large amount of literature written on the giving of feedback and its importance. A quick web search will reveal a large number of useful sites. The following information is based on the following web sites and references:

http://www.brookes.ac.uk/services/ocsd/firstwords/fw21.html

Gibbs G, Habeshaw S, Habeshaw T (1988) 53 Interesting Ways to Assess Your Students, Wiltshire, Technical & Educational Services Ltd

Kolb D (1984) Experiential Learning, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

Rogers Jenny (2001) Adults Learning Buckingham: Open University Press

Why give feedback?

Spend a few minutes thinking about this and jot down your ideas.

Learning is considered to be an active process (Kolb 1984). To learn, we need to plan what we're going to do; attempt to do it; and then receive feedback on our work. The feedback received is then used hopefully to improve subsequent performance, thus embracing any learning. Feedback is thus forward looking, focused on previous work, it must be constructive to be useful. It is important therefore to be given regularly, not just when things go wrong. Practice educators in their role can help students compare their performance with an ideal and identify their own strengths and weaknesses. The idea is to support the student in finding their own way of correcting problems, rather than doing all the work for them. Feedback will affect how we feel about our work and ourselves; thus affecting motivation.

How Do You Start?

Rogers (2001) says that the focus of feedback should be the work not the person. In giving feedback, whether positive or negative, fact and description should be given and not opinion. When giving feedback BE HONEST!

The Open University (OU) have done a lot of work on giving useful feedback to students. They have developed the 'feedback sandwich' approach. This involves giving the recommendations/negatives wrapped in praise.

- First, give the good news.

Students need to know what they've done right, orwell, and why it was good.This is important so that they'll keep on doing it right or well, rather than doing it well by accident. In addition it makes them feel good about themselves, motivated about their work and this itself aids learning.

Good news needs to be:

Clear Say what you think, if it was 'great' or 'excellent', then say so.

Specific Words like 'great' or 'excellent' are emotive, so when the emotional buzz fades, more details are required. So say exactly what and why it was good.

Personal Make the person you're giving feedback to feel acknowledged as an individual. Using their name in the feedback helps.

Honest As well as truthful, honest good news clearly distinguishes between fact and judgement. Be clear what the nature of the good news is.

2. Next, give the bad news - constructively!

It is equally important for students to know what they've done wrong, or what was inappropriate in their performance. This should be done in a way so to recommend areas of improvement or change, rather than telling students what they have done wrong. Feedback should be given immediately as students need to know why it was wrong or inappropriate. This is to prevent a repeat of the error and to identify the misunderstanding which led to the error. In addition suggestions on ways to improve or correct performance should be given. Negative feedback has a much more powerful impact on students. Only use negatives where appropriate and always back them up with suggestions on how to do better next time.

It is equally important for students to know what they've done wrong, or what was inappropriate in their performance. This should be done in a way so to recommend areas of improvement or change, rather than telling students what they have done wrong. Feedback should be given immediately as students need to know why it was wrong or inappropriate. This is to prevent a repeat of the error and to identify the misunderstanding which led to the error. In addition suggestions on ways to improve or correct performance should be given. Negative feedback has a much more powerful impact on students. Only use negatives where appropriate and always back them up with suggestions on how to do better next time.

Bad news needs to be:

Specific Make it clear in what respects the work is wrong, inappropriate.

Constructive Suggest how the work could be improved, give sources of information and guidance. It is important also to offer encouragement.

Kind Specific is kind. Constructive is kind. "Poor" scribbled at the bottom is cruel.

Honest (See above under 'good news')

Finally, end on a high note of encouragement.

Round off your feedback with a high note and encouragement. Say whatever you can that's encouraging and truthful. There's usually something that meets these two criteria.

Conclusion

A feedback session should result in the practice educator and student agreeing what is to be done to build on success and correct any mistakes. Hence it is necessary to make sure the feedback has been heard, understood, and will be acted on in the future. This can be checked with the use of open questions towards the end such as "Would you like to summarise what we have agreed?" or "How are you planning to put all this into effect?" It is best to avoid closed questions such as "Is that alright?" or "Have you understood?" As most people will simply answer "Yes" even though they have their doubts about what they are supposed to be doing.

Informal supervision and feedback

Informal supervision can take place at any time. For students to explore practice in your service setting you need to actively encourage him/her to observe, participate, question and reflect. You need to be able to communicate openly and clearly with the student and, as described in Part One, allow him/her access to your clinical reasoning. You will need to suggest when, and how, such discussion and questioning is most appropriate - for example, avoiding discussion of individual cases in public places. You will need to consider whether, at least initially, you would prefer not to have your practice questioned in front of a service user. In some cases it can help a student to become more thoughtful by turning his/her question around, and asking, 'Why do you think I'm doing things this way?'

Whether given informally, or in a session specifically set aside for that purpose, the effectiveness and outcomes of supervision will depend on a number of factors. These include:

- the model of supervision adopted

- the relationship that you develop with the student

- the stage of the student's development.

Models of supervision

There are three models of supervision, which are most commonly referred to in the literature: the apprenticeship model, the personal growth model and the educational model. Each of these has different characteristics, and may have different outcomes for the learning of the student.

The apprenticeship model

Using this model of supervision, the focus is on the experience and expectations of the service setting rather than on the needs of the student, with the student learning to operate in the same way as the practice educator. This can lead to difficulties in understanding for the student if the service setting is unfamiliar, particularly if the practice educator is unwilling, or unable, to fully talk through all aspects of his/her work and the particular approach adopted by the service.

The personal growth model

This model is based on psychodynamic and psychotherapeutic principles and regards the development of the student as therapist to be dependent on his/her self-awareness and personal growth. The focus on the student as an individual may lead to a lack of instruction and guidance in the more practical aspects of service delivery, particularly in the early stages of professional practice.

The educational model

In this model the focus is on the educational aims of the student and his/her learning. Although, as practice educator, you have to balance the needs of the student against service users' needs, this approach can incorporate the advantages of both the models above, promoting both professional and personal growth - not just for the student, but for yourself as well. This is the model of supervision preferred by many universities, including Liverpool.

![]()

As a practice educator, you will need to develop your own approach to supervision. This is likely to be affected by your own experience of being supervised, by personal attributes and by your professions custom and practice.

Watch again the video clips:-

Watch again the video clips:-

http://www.liv.ac.uk/healthsciences/pg_movies/OT_1.wmv

http://www.liv.ac.uk/healthsciences/pg_movies/OT_3.wmv

The two scenarios show contrasting approaches to the supervision session.

What differences do you notice in the relationship between the student and the practice educator?

What differences do you notice between the structure and content of the two sessions depicted?

In what ways does the practice educator in each clip promote student learning?

Which approach to supervision do you think is likely to be more effective - that shown in Scenario 1 or that in Scenario 2? Why is this?

Write down your comments about the two scenarios, replaying the video if necessary. Some notes, rather than answers, can be found in SR7, and more detailed information on the supervisory relationship and the use of the supervision session is found in the remainder of this section.

The supervisory relationship

The quality of the relationship developed between student and practice educator, is identified by students and staff as the single most important factor contributing to effective supervision. You will need to acquire the skills of teaching, supporting and discussing the progress of a student through supervision, and develop confidence in using these skills. As you saw in the video clips, how supervision is conducted, and the degree to which you direct and dominate the student's experience, is likely to have a significant effect on the student's ability to learn.

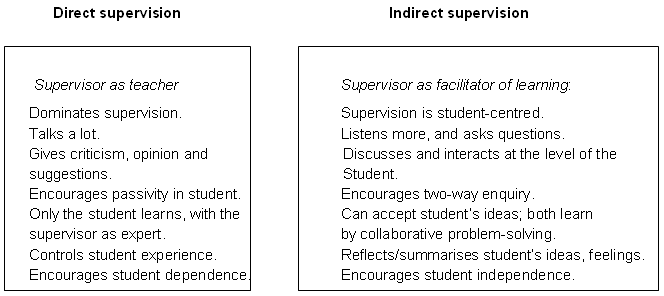

At its extremes, the degree of direction and its probable effect on learning can be represented in the tables below:

There is some evidence that less experienced supervisors tend to expect the student to take a more passive role during supervision. A more experienced practice educator will see having a student as a collaborative venture. Your aim will be to encourage the student to be an equal partner, able to take the initiative in discussion and to communicate his/her learning needs. You will need to have the confidence to admit you do not have all the answers, and be prepared to work with the student to find them.

Just as you may find your approach changing, student requirements will vary too as they progress through the course, and according to their previous experience. Early in their practice placements, students may benefit from more structure and direction in the supervisory relationship. As they progress, they will need to develop the ability to work with less direct supervision and you will need to be prepared to allow them greater autonomy.

Learning preferences might be reflected in your teaching as a practice educator. Furthering your own education, for example through CPD courses, you may become aware of other ways of classifying learning and teaching styles. These styles and preferences can similarly affect your approach to supervision. While it is clear that there is no one correct way to supervise, you should remember that individuals learn in different ways. Ignoring, or being unaware of, the student's feelings and preferences, and how they affect his/her ability to learn, may be an important source of 'personality clash' between student and practice educator.

While the relationship between student and supervisor can be a source of stress, you should remember that the student may be uncomfortable or even anxious not because of you, but because of your service setting. S/he may not have come into your work environment willingly. Your role is as an educator of the student, not as his/her therapist, and stress caused by the work situation is a problem for your employer, and not for you. It is important that you do not see yourself as solely responsible for educating the student in professional practice. You should ensure that you yourself have the support of a mentor with whom you can share professional practice supervision issues.

The supervision session

The supervision session is more than a simple monitoring of student progress - it is crucial in facilitating the student's growth as a professional. S/he needs to be educated to take on the role of a partner in this process, not just in terms of the individual placement, but as a skill which will be required throughout his/her professional life. Should you be carrying out a formal supervision session, the following principles should be considered.

Supervision sessions should be planned in advance, giving both you and the student time to prepare. The session should be as undisturbed as possible. You may agree an agenda ahead of time, to ensure that specific areas are covered, or that there is a particular focus to your discussion.

Supervision sessions may include the following:

- Reflection and feedback on the week's activities

- Reviewing of student achievement and progress

- Revision of learning objectives/the learning contract/setting further goals

- Exploration of practice issues

- Formative assessment/halfway report.

During supervision the student needs to explore experiences - what happened, what went well, what might be done differently? Having the student keep a 'learning log' of placement experience can be a useful tool to aid reflection at this time. Students may be required by the university to keep a reflective journal or a portfolio, or they may be given material to act as 'prompts' for reflection and in evaluation of their own performance. It is advisable for you to keep a supervision log, to record the main areas discussed, learning objectives set, and decisions taken - for example, to allow a student to undertake a treatment intervention alone.

As in informal supervision, the role of the practice educator can take many forms - testing the student's knowledge, challenging assumptions, helping him/her find other solutions and think through the consequence of his/her actions, suggesting resources, and showing how knowledge might be applied in other situations. With a more experienced student, supervision can also be used to explore the links between theory and practice.

Some practice educators use 'experience checklists' to give more structure to supervision sessions, as well as the learning contract/assessment form. Warrender (1990) developed a learning package for this purpose which covers four areas - communication, the treatment process, treatment relationships, and organisational management and administration - and which assumes that the student will progress from the level of observation and orientation, through understanding and participation, to responsibility and proficiency.

Such checklists, and the supervision log, will be useful if you are absent during your student's placement and supervision has to be carried out by a colleague. The lists might also be of use to supervisors in other service settings, which your student may visit.

![]() What might be achieved through the supervision session - for the student and for yourself?

What might be achieved through the supervision session - for the student and for yourself?

How will you facilitate the student gaining understanding/insight of self in developing professional identity as a health care practitioner?

What strategies will you use to facilitate, guide and encourage growth of student?

Spend a few minutes considering the questions. Jot down your ideas, and compare them with the notes on SR8

We hope that you are beginning to see how the ideas and exercises in all the sections in the pack are beginning to draw together, to guide you in becoming an effective practice educator. They should help you to:

- Understand how individuals learn

- Provide an environment conducive to learning

- Manage the professional practice experience of a student

- Relate a student's learning needs to your service setting

- Create and recognise appropriate learning opportunities

- Facilitate student learning

- Provide support and constructive feedback

- Ensure that learning has taken place.