Crozet worm blog

18/12/05

by Adrian Glover

What am I doing in the middle of the Southern

Ocean, 1000 miles from anywhere, collecting worms? And in

particular, why should anyone care about worms from the Crozet

Islands of all places? Despite the occasional few minutes

of self-doubt, lying awake at night in my cabin aboard RRS

Discovery, I can, I think, answer this question. For one thing,

it turns out that worms are rather more common than you might

think. The earth’s surface is over 60% ocean, and take

any sample of the seabed of that ocean – with a bucket,

trawl, or dredge – and the chances are you will bring

up a large handful of worms, especially polychaetes –

marine segmented worms which are known for their ‘hairy’

appearance. These things are so dominant in the marine realm,

that an alien from outer space, randomly sub-sampling planet

Earth for life, would most likely bring up a load of polychaetes

in their first samples.

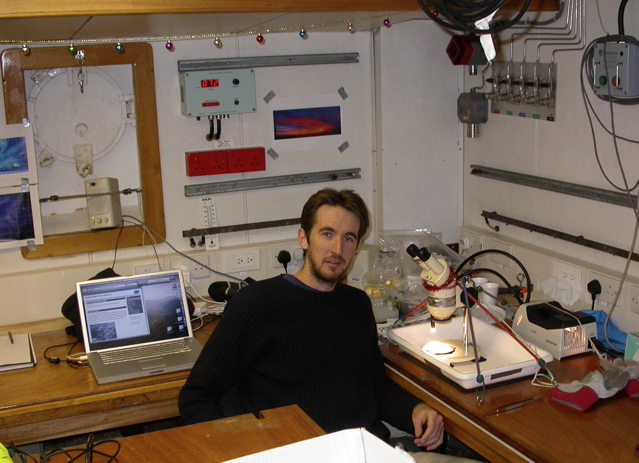

The ‘worm’ lab…

So they are common, but what do they do? And

most importantly, why should anyone care? This question can

be answered in two ways. Firstly, because the abyssal plains

(such as those around the Crozet Islands) are so remote and

difficult to sample, we have really very little knowledge

of this group of organisms. So, for the most part, we don’t

know what they do. But the research that has been carried

out shows that they are incredibly biodiverse, with perhaps

thousands, even millions of undescribed species in the deep

sea. The first step in understanding an ecosystem is to describe

the animals that live there, and to compare these new species

with those we have found from elsewhere. This gives an idea

of the ‘community’ of animals living in this region,

and how similar – or different – it is to other

places that we know much better. Describing these new species

also allows us to place them in their evolutionary context,

on the ‘tree of life’, which helps us to understand

how and why these things evolved in the first place.

Somewhere in this bucket is a worm that

is going to change the world!

The second part is perhaps more complicated.

What function do these worms perform? Worms that live on abyssal

plains, 4000m from the surface of the ocean, are detritivores,

consuming ‘detritus’ (dead organic-rich material)

that has fallen from the surface layers of the ocean, where

photosynthesis takes place. Hence they perform the rather

important function of recycling organic material at the seafloor.

The abundance and community structure of the worms, can help

us to understand the processes occurring in the ocean above.

We can measure various wormy parameters (e.g. how abundant,

how many species, what function they perform) and compare

this with what we know about the biology of the ocean above

them.

The USNEL spade box core. Advanced ‘bucket

and spade’ technology.

So that is the reason I am here. There are worms

down there, and somebody needs to sort them out. One of the

other cool things about polychaetes is that they are actually

quite pretty. So here are some pictures of polychaetes (taken

down the microscope) from our recent trawl and box core samples

at station M5:

A large scale-worm from the abyssal plains of Crozet. |

A cirratulid polychaete brought

up in a box core.

A cirratulid polychaete brought

up in a box core. |

This large, onuphid polychaete

is abundant in our trawls and lives in muddy tubes.

This large, onuphid polychaete

is abundant in our trawls and lives in muddy tubes. |

|

Click on the

pictures for a larger version. Opens in new window/tab |

|