| << |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

31 |

5/1/2006 Worms of the Deep

By Robin Floyd

|

Today

it’s my turn to say a bit about myself and why

I’m here on board the Discovery. Actually this

is a question I’ve asked myself a few times,

considering I’m one of the few people here with

pretty much no experience in marine biology or oceanography,

and who has never been to sea before; finding myself

aboard a research vessel in some of the remotest waters

of the world is not something I ever expected. By

training I’m a molecular biologist (meaning

that I work with DNA), with a particular interest

in applying DNA-based techniques to studying the biodiversity

of small and obscure animals. My PhD was on nematode

worms in agricultural soil, for which my fieldwork

never took me further than 60 miles from Edinburgh.

|

Then, as I was finishing

my thesis, the British Antarctic Survey and the Natural

History Museum were beginning a collaborative project

to study the nematodes living in deep-ocean mud. I

was employed as a postdoc at BAS, and that, to cut

a long story short, led me here to collect samples,

along with Margaret Packer and Adrian Glover from

the NHM, who are involved in the same project. |

An unidentified nematode from

one of our samples (photo courtesy

of Adrian)

An unidentified nematode from

one of our samples (photo courtesy

of Adrian) |

|

So why

are we interested in nematode worms? Well, they may

be small (around 1mm long on average), but they have

strength in numbers. A typical square metre of topsoil

may contain a million individuals. Similar numbers

seem to exist in marine sediments (though far less

is known about distributions there), and when one

considers that seven tenths of the Earth’s surface

is covered by water, and much of the remainder by

soil, it becomes clear that nematodes must account

for a substantial fraction of all animals on the planet.

|

| In variety of species,

too, they surpass all other animal groups (with the

possible exception of insects) – though all

nematodes share the same basic body plan, they have

evolved into a wide range of forms, filling many different

ecological niches. There are around 12,000 described

nematode species, but this is undoubtedly an underestimate

of the real number, since every survey of a new environment

unveils a multitude of new ones; the true total is

likely to run into the millions. |

| Why does

this matter? If there’s a common thread that

ties together all of the disparate research activities

we’re doing on this voyage, it’s understanding

natural ecosystems, the varieties of life which make

them up, the cycle and flow of nutrients and energy

from one level to another. Given the rate at which

human activity is altering natural processes, we consider

it important to understand these systems, given that

we all depend on them for our survival. What we know

about nematodes, put simply, is that there are a lot

of them, they eat a lot of different things, and a

lot of different things eat them. |

|

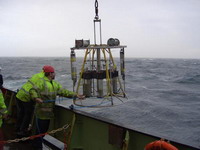

The megacorer, on a day when it decided to bring up

some material… |

This makes them a significant

component of ecosystem function, one about which relatively

little is known compared with other groups. Therefore

we wish to know more; however, those numbers I mentioned

earlier should give some idea of just how difficult

it is in practice to build a realistic picture of

how many species exist and how they are distributed.

The problem is exacerbated by the fact that nematode

taxonomy - the identification of individuals to species

by examining their physical features down a microscope

- is extremely difficult and laborious. |

Adrian and Margaret slicing a

core into horizontal sections

Adrian and Margaret slicing a

core into horizontal sections |

Hence,

DNA barcoding, which is my particular specialist subject.

Rather than identifying an animal by its morphology,

it is possible to read a particular segment of its

genome, then, by comparing many such segments from

different individuals, to use that information to

tell us how many types are present; this is potentially

far more rapid than traditional taxonomy (though the

DNA approach has pitfalls of its own, but that’s

another story). The hope is that this will enable

us for the first time to generate some broad-scale

data on nematode biodiversity, especially in environments

such as the deep ocean where they have seldom been

studied before, and to begin to answer some of those

basic evolutionary and ecological questions. |

| So

that in essence is why I’m here, braving the

cold and the waves, sifting through mud from 4000

metres below, and trying to do molecular biology in

a lab which is constantly rolling from side to side.

Of course, the main part of the DNA work will be done

back on land; Margaret and I are really only collecting

and preserving the animals while we’re on ship.

I’ve been learning some microbiology as well

– when I haven’t had any nematode material

to work with (that megacorer is a temperamental thing),

I’ve been assisting my BAS colleagues David

Pearce and Rachel Malinowska with their work on seafloor

bacteria. All in all, I may have found myself somewhere

I never expected to be, but I wouldn’t be anywhere

else. |

|

Me, on deck

|

Me, sieving for worms |

|

|