- Introduction

- Material Culture Studies: A Brief Introduction

- Origins of Authority - The Development of Museums

- Countering the Authority of the Museum

- Library Resources

Introduction

Museums are the primary sites in Western society at which people have contact with the material culture of the past and of other societies around the world. They are hugely diverse, ranging from the vast institutional gravitas of the British Museum and other national collections to the small and highly specialised (sometimes highly eccentric) museums that exist all over the world. The sheer number of museums testifies to the enduring significance of material culture in human life - and more pertinently, to the importance of telling the story of human existence through collections of objects. In this lecture, we will be considering some of the key issues centring on museums and their role in society. They include (with some overlap)

Institutional authorityThe legacy of private collections, cabinets of curiosity, world fairs and the Great Exhibition The dynamics of display: how displays are constructed and the analysis of overt and covert messages Representation and constructedness Some case studies

Material Culture Studies: A Brief Introduction

Archaeology is concerned with material culture, but, more obviously, what it 'means' and what to say about it; "The objective past will not present itself" (Shanks and Hodder, 1995). The question of meaning is itself a fraught one. Can we ever really hope to understand what an object meant in its original context: to its maker, user, in the context of other objects etc? In that sense, the attempt to define meaning is more accurately an activity that interprets the object within the present construction (consensus?) of 'knowledge' about the past; archaeology (through writing etc) is a mode of production of the past (11:ibid).

In museums, the meaning of objects is further complicated by the multiple contexts operating in the museum space, at, for example, institution, gallery, case and text level. Museums use various strategies for presenting and interpreting objects; some overt, like captioning, and some covert, like the selection of objects to convey a particular impression. (Susan Pearce's work should be consulted as the definitive account of meaning-making in museums eg: Museums, Objects and Collections 1992:146).

Objects embody unique information about the nature of man in society: the elucidation of approaches through which this can be unlocked is our task, the unique contribution which museum collections can make to our understanding of ourselves (Susan Pearce, Museums Journal).

The museum communicates values in the types of programmes it chooses to present, and in the audiences it addresses, in the size of staff departments and the emphasis they are given, in the selection of objects for acquisition and more concretely in the location of displays in the building and the subtleties of lighting and label copy. None of these things is neutral. None is overt. All tell the audience what to think beyond what the museum ostensibly is teaching (Vogel).

Origins of Authority - The Development of Museums

Large private collections of individuals and families whose wealth, influence and power provided the means and motivation for amassing prestigious collections - eg Habsburgs of Austria (1400s onwards).

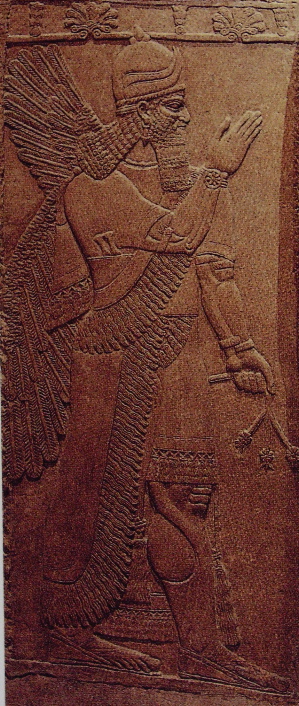

AlsoCabinets of Curiosity rare, exceptional, extraordinary, exotic and monstrous thing (Pomian, 1990)

Heyday at end of Middle Ages - flourished from 1550, rare from 1750 on.

Between 1556 and 1560, contemporary collector listed existence of 968 collections in Netherlands and central Europe. Not all the same, but shared some basis similarities. Founded on medieval scholasticism, looking at innate nature of world and things, relationship of world in microcosm and macrocosm.

Note emergence of some important principles:

- Universal/encyclopaedic quality

- Classification of objects

- Symbolic representation of the world in miniature

And controlling rationale implies authority of the collector/institution.

Travel and Discovery - Possessing the WorldExploration brought whole new opportunities for acquiring and possessing curious objects. Collecting signifies both having been there and having come back safely. Eg The Great Exhibition (of the Industry of all Nations) 1851. Comprised objects and materials from all over the Empire displayed to underline Britain. Reflected immense global power and prestige.

No alien, of whatever race he may be - Teuton, Gaul, Tartar or Mongol - can walk through the marvellous collection at South Kensington and look at the innumerable variations of our national Union Jack, without feeling the enormous influence that England has had, and still has, over every part of the globe (The Graphic, 8th May, 1886).

Note - because museums are so effective at asserting the authority of their own message, they have been adopted by various groups as a model for promoting their status, identity etc Eg Emerging nation states establishing national museums, or oppressed cultural groups collaborating on museum exhibitions (consult Kaplan, F (1996) Museums and the Making of Ourselves)

Te Maori (1980s - large exhibition of Maori artefacts in big Western galleries (Metropolitan Museum of Art etc); lots of collaboration with Maori elders, rights of veto over all objects, Maori ceremonies etc ; but still lots of controversy. But who is entitled to speak for a cultural group?

But also weirder examples:

Eg: Creationist MuseumsEvolution in opposition to the beliefs held by certain evangelical Christian groups, who believe that the World was created in six days and not millions of years ago. In America particularly, these groups are well coordinated and resourced.

Have started setting up creationist museums that present the 'scientific evidence' for the creationist view of the world

For example

- 7 Wonders Museum, Washington State

- Creation Evidence Museum

- Genesis Park

- The Creationism Organisation

Countering the Authority of the Museum

Museums as sites of debate rather than didacticismFor example - The Wellcome Wing at the Science Museum, London, provoked controversy in the museum world as to whether science can be meaningfully debated by laypeople.

Museums as Sites of Memorialisation/AcknowledgementThe Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg - We have children here who don't believe apartheid happened Visitors are given cards identifying them as either white, or non-white, regardless of their actual skin colour. They are then sent through separate access corridors. The Museum has 121 nooses hanging as a display - one for each political prisoner hanged under the regime.

The Holocaust Museum, WashingtonTraditionally museums are places of celebration, presenting cultural achievement or the wonders of nature or science. The horrifying quality of Holocaust material does not transform such a context: rather, it is transformed by the context

The Smithsonian - the display of the The Woolworth Counter, Greensboro, North Carolina

1950s and 1960s - Civil Rights Movement in America. In 1960, 4 African American students defied the segregation rules in a Woolworths store in the southern states (which remained racially intolerant). Blacks were not allowed to sit and eat at the lunch counter, only to buy food to take out. The 4 students carried out a sit-in at the counter, asking to be served (but being refused) and refusing to leave when asked. Over a period of 6 months, many more people joined in with this protest. Finally, in June 1960, the lunch counter was desegregated. The lunch counter was later bought and exhibited at the Smithsonian.

Yeingst and Bunch write about this

As curators, what we collect, whose stories we preserve, what interpretations we present, and our mandate to convey those decisions to millions gives us power. The power to determine who and what has value. The power to save or to forget a people's culture. The power to shape memory. And the power to help determine what is historically meaningful and culturally significant. In essence, curators have the power of choice and the power to convey meaning - powers that should be used judiciously and openly (Yeingst and Bunch1997).

A key question raised by the above is whether museums can ever really relinquish authorial authority in institutional practices steeped in power inequalities, Western-centric ideologies and through strategies that are resistant to change.

The museum context is quite difficult to subvert; the dynamics of display are often covert, subliminal, intangible, culturally ingrained. Sometimes, curators commission installations that are slotted in and amongst existing displays, aiming to disrupt their self-contained control.

For Example

- Victoria and Albert Museum - sculptures of physically disabled people placed amongst classical statues.

- Pitt-Rivers. Joachim Schmid Collection Installation - postcards placed in display cases. Postcards act as found objects. It is not clear who is the author. They are also typical of Western throw-away ephemera, a means of broadly disseminating ideas.

- Problems with Te Maori, in spite of extensive consultation

- Liverpool Museum - consultation with focus groups during development of new World Cultures Galleries. Caused quite a lot of suspicion and cynicism about motives of the museum (Why are things coming out now? What are they telling us?, etc).

- ExitCongo. Attempt to realign displays of Royal African Museum in Belgium. These displays are a legacy of Belgium's often brutal colonial rule of the Congo region of Africa. The curator, Boris Wastiau, redisplayed objects to emphasise their formal aesthetic qualities (as works of art), added context with regard to their modes of acqusition, and commissioned artists (African) to add their own insights.

even though any discussion of African objects is usually one-sided and ethnocentric, ways do exist to replace them as well as possible in those social and historic contexts which have together contributed to the formation of their global meanings, and thus to let them speak (Wastiau, 2001).

Wastiau sees museums as places where issues like representation can be problematised. You can foreground the problems inherent in owning, inheriting, interpreting etc other cultures and material objects. Hence it becomes possible to open up the debate; and even to offer resolutions to the inherent tensions in these practices.

Maybe the first question to ask is why Africa and its inhabitants should be represented in a museum? What association should be made between the never neutral cultural representation and the political economy of cultural properties?

Wastiau sees museums as contact zones for the disparate parties involved.

To end with two additional insights:In addition to marking social changes, the objects in our collections can be seen to play an active role in changing social relations (Herle, 1997).

but

Until museums do more than consult (often after curatorial vision is firmly in place), until they bring a wider range of historical experiences and political agendas into the actual planning of exhibits and the control of museum collections, they will be perceived as merely paternalistic by people whose contact history with museums has been one of exclusion and condescension (Clifford, 1997).

Link to the ALGY 399 Sydney Jones Library Reading List.