- Introduction

- Individual Collections and National Museums

- The World System and the Flow of Cultural Property

- The Acquisition of Cultural Property Today

- Library Resources

- Internet Resources

Introduction: humans as collectors

Recent surveys indicate that at any one time approximately one third of all individuals in the First World are actively collecting material things. If this number were to include all those people who have collected during their life it has been estimated that this figure would probably rise to over a half of all individuals. The collection and use of material objects for its own sake goes back to at least the Bronze Age, whilst the collection of interesting artifacts by individuals can be traced back to the curiosity collections in the sixteenth century. Collecting and collections of objects, therefore, are significant ways in which we both use our 'financial' resources and make sense of our lives to ourselves and other people. From an archaeological perspective the practice of archaeology is a specialised form of collecting (the collection of past antiquities from a specific context). Whilst archaeology also has a rather complicated relationship with patterns of collecting by museums and individuals in general.

There is a long history of the collection of antiquities, which goes back to Roman times. In Medieval times, relics of saints were sold to the highest bidder, and unscrupulously used as mechanisms for attracting donations, etc. The major change, however, happens with the 'rediscovery' of the Ancient World and the development of the Grand Tour as a complement to the classical education. A classical education, including the learning of Latin, ancient Greek, ancient philosophy, ancient history and an appreciation for classical architecture was considered essential for the making of a well-mannered gentleman. Sons of the landed gentry and, later, the middle classes began to go abroad to have their education finished by their direct appreciation of the great treasures of the Ancient World. In this way the grand tour was born. An inevitable consequence of the Grand Tour was the increase in books and pictures bringing images of the Ancient World to popular attention. In addition to this, gentlemen who went on the Grand Tour often brought parts of the Ancient World back with them.

In addition to the copying of classical architecture, and material culture in the Neo-Classical revival (from 1765), original antiquities came home in the form of souvenirs collected by individuals. Large-scale acquisition of cultural properties can be traced back to the military campaigns of Napoleon in Egypt and Europe. Whilst many of the finest treasures were acquired during periods of colonial rule by the major European countries. Our major museum collections are the result of collection policies by individuals or families. Some major archaeological sites were excavated specifically for the purpose of providing collections for museums.

Individual Collections and National Museums

Most of the major museums are based on great collections of individuals and families that have been 'donated' to new museums and then opened to the public. From this initial base, most museums are now also still major collectors of objects and antiquities.

The Ashmolean Museum, was the world's first public museum. It was opened to the public in 1659, and is based on the natural curiosities collected by the Tredescant family.

The British Museum is based originally on the collections of Sir Hans Soane, Duke of Oxford, and member of the Society of Antiquaries. The Society of Dilletanti met in the Museum store rooms. They were more like a sort of cluttered clubroom than a storeroom at this time, and there the Society of Dilletanti read, talked, dined and enjoyed the ambiance of the great antiquities. There are also the collections of William Hamilton and the famous penis cult of Priapus, only just returned to 'show'.

The Danish National Museum in Copenhagen - derives originally from the collections of the Danish Royal Family. The Museum is very rich in prehistoric materials, with a strong sense of seafaring and the Vikings.

The French National Museum (The Louvre) derives from the collections of the French Royal Family.

The British Museum of Natural History, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London originally started with the collections brought together by Prince Albert - husband of Queen Victoria, for the Great Exhibition of 1851, held in Crystal Palace.

There are still major museum collections still on the collections of favoured individuals. The best known examples in the UK are; the Wallace Collection in London, that houses major collections of ceramics and East Asian antiquities, and the Burrel Collection in Glasgow, based on the vast collections of a Clydeside shipping magnate.

Some museums are the result of special collecting activities.

The Pitt-Rivers Museum, Oxford (now one of the University museums at Oxford), contains collections acquired by Augustus Henry Lane Fox - later Pitt-Rivers. Pitt Rivers collected and displayed artifacts to illustrate his ideas on cultural evolution and progress.

The World System and the Flow of Cultural Property

Extensive trade in material goods can be seen from the appearance of the first state civilisations in the Near East, and continued through the rise and fall of the classical civilisations. Since the beginning of the Medieval period (approx. 1000 AD) there has been a massive increase in the scale of travel and trade, such that from the 16th century it has been possible to talk of a genuine world system of trade, travel and colonisation. The economic disparity between the countries and people of the first world also dates from this period. From the sixteenth century onwards we also see the beginning of the European colonial empires, Spain, France, Portugal, Belgium, more recently Germany, and of course the British Empire. With the decline of Empires through the nineteenth centuries and especially the twentieth century, the political influence of governments has been replaced b y the strength of market forces in the movement of goods (including cultural properties) around the world.

One of the effects of this long-term process has been the steady movement of collected cultural properties from poorer people and countries to those more wealthy. In the beginning of empire this might have been achieved through political / diplomatic agreements and military conquest, to collect and acquire goods. More recently the influence of the 'open market' has seen the simple movement of goods from their place of origin to the place where there is the greatest demand and the highest price might be paid. This relates to both individual collections and to collections made by museums.

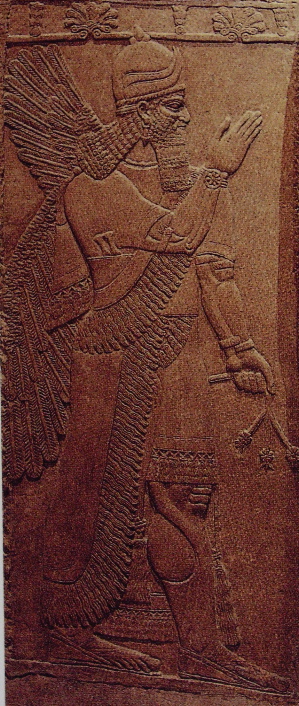

As a result of this process, there are many a number of single artifacts and collections of artifacts that might be considered to be the priceless national treasures of poorer countries (or countries that were previously poor) in the possession of museums and individuals in wealthier states. Some classic examples include the Parthenon ('Elgin') Marbles, the Benin Bronzes and the Assyrian Palace reliefs from Nimrud and Nineveh. Single objects include the Venus de Milo, the Winged Venus of Samothrace, the bust of Nefertiti, and so forth. Not surprisingly a number of countries would like cultural treasures of this quality returned to their place of origin.

The Acquisition of Cultural Property Today

The collection of cultural property / antiquities is not a thing of the past. Every year more antiquities are sold. The direction of the antiquities trade is still predominantly from the poorer nations to the richer nations. Cultural properties pass through the hands of both specialised dealers in antiquities as well as the great auction houses, such as Sotheby's, Christies and Phillips.

Each of these auction houses sells ancient and ethnographic art, and antiquities as a sub-section of this group. Sotheby's and Christies also have online auctions of antiquities. Try looking at Sotheby's on ebay. Antiquities are also sold in small shops and in markets. For example, if you walk around the Sunday market in the rich suburb of Rosebank, in Johannesburg you can buy antiquities from East Africa, bronzes from Nigeria (Benin style), ancient metal exchange items from East and West Africa, antique ethnographic Masaai items, and so on. Similar markets exist in the other tourist centres in Zimbabwe, Malawi, Kenya, etc. Antiquities are purchased by individuals, institutions and museums. The main nations involved in the sale and purchase of antiquities include the USA, the UK, France, Germany and Switzerland. There are also a number of individual collectors in Japan.

Each of the major auction houses has sales of antiquities along with their usual art and furniture sales, etc. Some of the objects sold at these sales are the collections of individuals being sold on after death or change in interest. Others are objects that have recently come to the market with less clear provenance. Auctions now include not only those held at the offices of the auction houses themselves, but also virtual auctions held over the internet. It has been estimated in a recent report to Parliament that in the UK alone, the antiquities market is worth £4 bn each year. It has also been suggested that in the USA there are at least 2000 collectors of antiquities who spend more than $ 50,000 on average per annum. As part of this sales process, many artifacts carry letters of authenticity (as to age, authorship, style) provided by academics and experts in museums, etc. These details can considerably influence the price paid for objects.

The demand for antiquities, and the money spent on their purchase each year has resulted in the looting of many archaeological sites and museums in countries all around the world to supply this demand. Turkey estimated (in 1995) that it was losing more than 100 million sterling of antiquities alone each year looted from archaeological sites. Looting is a particular problem in Mali (West Africa), Nigeria, and even the USA. The National Museum in Kabul (Afghanistan) has been successively ransacked to the point of almost complete loss since the start of the wars in 1979. There has been a dramatic increase in the sale of Iraqi antiquities, since the imposition of United Nations sanctions against contact with Iraq following the Gulf War in 1991. Many antiquities are stolen to order. They move along a chain from an original '' or thief, through intermediaries until the final purchaser. There are examples of professional looters of tombs (in Italy, for example). There are examples of intermediaries who are passing on thousands of antiquities (see the examples in the journal Culture Without Context). There is also evidence that many antiquities are receiving false provenance details through the actions of unscrupulous dealers. It is also clear that many dealers and auction houses have 'turned a blind eye' to such false provenance details. It is also clear that there are links between the theft and resale of antiquities and organised crime networks.

The looting of archaeological sites and museums both irreparably damages the archaeological record of looted countries, and also impoverishes museums to the extent that they cannot easily present their own historical cultures. Both archaeologists and others would like to see the end of the looting of sites, and museum officers and governments would like to keep their own treasures safe. This will require mechanisms to return looted treasures and to intervene in the art market more fundamentally.

The UK is one of the major centres for the antiquities market and it is clear from recent studies that there have been numerous occasions in which antiquities have been smuggled into the UK, and when the auction houses have connived in the falsification of provenance details for artefacts. The Department for Culture, media and Sport (in the UK government) recently commissioned a ministerial advisory panel report on the illicit trade in antiquities and its occurrence in the UK.

Library Resources

Ames, M.A. 1992. Cannibal Tours and Glass Boxes: the anthropology of museums. Vancouver, UBC Press.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. 1999. Museums and the shaping of knowledge. London, Routledge.

Messenger, P.M. 1999. The Ethics of Collecting Cultural Property. Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press.

Pearce, S. 1995. On Collecting: an investigation into collecting in the European tradition. London, Routledge.

Pearce, S. 1998. Collecting in Contemporary Practice. London, Routledge.

Renfrew, A.C. 2000. Loot, Legitimacy and Ownership. London, Routledge.

Stocking, G.W. (ed). 1985. Objects and Others: essays on museums and material culture. Madison, University of Wisconsin Press.

Link to the ALGY 399 Sydney Jones Library Reading List.Internet Resources

The major museums can be found through the 24 Hour Museum website.

Both Sotheby's and Christies have web sites that detail their forthcoming auctions as well as providing links to internet auctions. Look up their sections on Ancient and Ethnographic Art to find troutes through to their sales of antiquities.

The full details about the illicit trade in antiquities that has so far come to light can be found in the journal Culture Without Context that is accessible online from the Illicit Antiquities Research Centre based at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research in Cambridge. They have an online exhibition entitled Stealing History. A printed version of this is available in the Student Resource Centre

The Archaeological Institute of America also takes a firm stand against the illicit trade in antiquities. They regularly report looting and illicit trade and museum purchases in their Archaeology Magazine. Try searching their site with the following keywords illicit antiquities trade or theft of antiquitiesto get access to more than 30 articles and links to the antiquities trade and looting of sites. They currently have a large spread on the looting of Iraqi antquities.