- Introduction

- What is Cultural Property?

- Why do Countries want their Cultural Treasures Returned?

- UNESCO Conventions for the Return and Protection of Cultural Property

- How can Cultural Treasures be Returned?

- How can Ownership be Retained ?

- Can the Antiquities Trade be Stopped?

- Examples of Repatriation

- Library Resources

- Internet Resources

Introduction

If we agree that cultural property and cultural treasures are important in the creation and maintenance of national identities, then it seems reasonable to assume that we should be in favour of the return of cultural treasures back to their place of origin, or importance. In the light of what is know about the acquisition of cultural property, we are, therefore, concerned with both the return of (i) properties that were acquired in the relatively distant past (such as the Benin Bronzes; as well as (ii) properties that are being acquired and traded at the current time. In the first instance we are dealing with ways of deciding which treasures need to be returned and to whom. These treasures have also often been sold / traded legally and they now reside in the hands of legal owners. In the second instance we are concerned with both stopping the looting of sites and museums, the prohibition of the current art market for these recently looted goods, and the return of those goods which have been sold to others. Many of these goods will have been initially acquired and later sold on illegally. Furthermore, in the first case we are almost always dealing with an international problem; whilst in the second case we are dealing with a problem that may be both national and international.

What is Cultural Property?

'Cultural property represents in tangible form some of the evidence of man's origins and development, his traditions, artistic and scientific achievements and generally the milieu of which he is a part. The fact that this material has the ability to communicate, either directly or by association, an aspect of reality which transcends time or space gives it special significance and is therefore something to be sought after and protected'

'For the purposes of this Convention, Cultural Property means property which on religious or secular grounds, is specifically designated by each state as being of importance for archaeology, prehistory, history, literature, art or science' (Both quotes from 1970 Paris Convention - see below)

- Moveable Property - 'mobiliers'

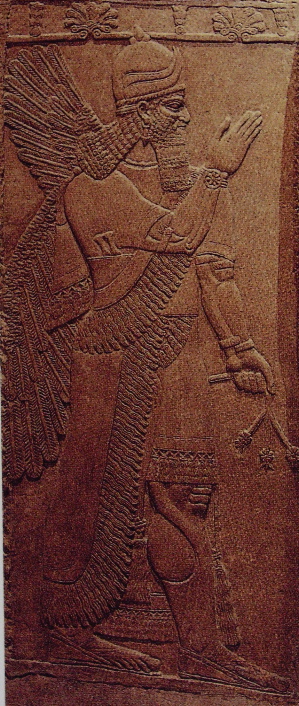

- Artifacts (Sculpture, archaeological remains)

- Skeletal remains and grave goods (such as the Ghost Shirt - originally in Kelvin Grove Museum in Glasgow - taken from the body of a dead Sioux warrior after the Battle of Wounded Knee in 1891 and returned March 1999)

- Intellectual property (Indigenous societies genetic material and sequencing, similar to patents, Indian lawyers have been protesting against foreign drug companies trying to patent the healing properties of the spice Turmeric, one of many)

- Immovable Property - 'immobilier'

- Parts of still standing monuments (temple facades, etc) - Parthenon Marbles, Benin Bronzes

- etc.

Why do Countries want their Cultural Treasures Returned?

There are a number of reasons why countries would like their cultural treasures returned.

- they are a central part of the formation of the identity of a new nation,

- nations use their cultural heritage to say something wonderful about themselves,

- cultural treasures are key artefacts in the encouragement and maintenance of a tourist economy,

- it is a matter of dignity

The major reasons why countries and museums do not wish to return treasures include:

- they were acquired legally in the first place and are, therefore, the property of current holding institutions,

- treasures are the property of all people and are best displayed in 'world museum' contexts,

- if you return one treasure you will have begun to slide on an ever more slippery slope leading to the return of all properties,

- the success / reputation of a museum is dependent on the importance of the objects that it holds in its collections

How has this cultural property been acquired in the first place?

- Legally - through purchase, or donation, excavation permits, etc.

- Illegally - through direct theft, war reparation, or purchase of stolen property.

But how do we tell / determine which is which?

UNESCO Conventions for the Return and Protection of Cultural Property

UNESCO has put forward numerous recommendations and Conventions. The most important are the 1954, 1970 and 1995 Conventions.

1954 Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (The Hague Convention)The Hague Convention rgues that treasures stolen during wartime should be returned to their original owners. Looting of museums by invading armies in WWII was the catalyst. Particularly important these days in view of the movement to return treasures taken by the Nazi armies from Jewish households before and during WWII. There is a working party chaired by Nicholas Serota, head of the Tate Museum, to help museums look through their collections for material that dates to these events.

1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (The Paris Convention)The 1970 Paris Convention states that a nation should define its national treasures in a list and then these will be protected if stolen. It provides mechanisms for states to recover stolen cultural property. But the nominated cultural property must be of national importance. This convention does not provide individuals or institutions with these rights, and so the convention needed support from another convention in 1995.

1995 Unidroit Convention on stolen or illegally exported cultural objects (The Unidroit Convention)The 1995 Unidroit Convention attempts to deal with the problems of the 1970 convention. It does so by recognising the rights of individuals and institutions to have their property restored to them (conceived at Venice).

How can Cultural Treasures be Returned?

Amicable return of ownershipThe return by Denmark of the "Codex Regius" (The Kings Volume) and the "Flateyjarbok" (The Book of the Flat Land) to Iceland.

By force of lawNative Indian and Aborigine skeletal remains and burial goods. The Lydian Hoard returned to Turkey from the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 1993. Attempts by 'owner countries' to stop the sale of stolen treasures. 1990 - Sothebys attempts to sell the Sevso Treasure. 1993. Aidonia Treasure sale stopped.

By perpetual loanReturn of the beard of the Sphinx

By personal actionRecovery of a Mayan codex from the National Library in Paris. The theft of the Stone of Scone stolen from Westminster Abbey.

How can Ownership be Retained ?

Purchase order allowing the host nation to raise the money The Three Graces by Canova Donations from heritage funds National Heritage Memorial Fund - The Churchill ArchiveCan the Antiquities Trade be Stopped?

Better laws forbidding the sale of antiquities through auction houses that have poor provenance. (If they have not been published prior to 1970, it is likely that significant pieces have been looted. Archaeologists and others who value antiquities need to be made more aware and, perhaps, more responsible for their actions.

Some well-known examples of Repatriation

The Aidonia TreasureIn the 1980s a series of clandestine excavations at the great Mycenean site of Aidonia produced at least 312 pieces of jewelry that formed part of a magnificent funerary treasure. they were smuggled out of the country and taked to the USA. In 1993 thhey were put on display in a New York gallery by a certain Michael Ward as a viewing for a proposed later auction of the items, supported by a lavish catalogue. Greece filed for the repatristion of these itesm in May 1993, on the grounds thhat they were similar to pieces legitimately excavated at the site of Aidonia and likely to have come from the the loot excavations from this site. Before he was forced to reveal the manner in whichh he had acquired the pieces, Michael Ward donated the treasure to the Society for the Preservation of Grek Heritage, who returned them to Greece in January 1996. Web based resources for the Aidonia Treasure have been provided by David Gill of the University of Wales- Swansea. Click here.

The Lydian HoardThis is probably the most famous case of repatriated antiquities in recent times. 363 artefacts (incl gold and silver artefacts, marble sphinxes, jewelry and wall paintings were acquired from 1966 - 1970 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art for $1.5 million. They were originally stolen from burial mounds in the Mansa and Usak regions of Turkey. The looters themselves were stopped in the process of stealing more, and so 100 artefacts were left behind. The looters were arrested, prosecuted and provided testomonies of what was stolen and to whom they had been sold. Minutes of the Acquisition Committee of the Metropolitan Museum show that the Museum knew that the Hoard had been stolen. They originally had plans to display the Hoard in 1970, but were put off and the hoard was not finally displayed unitl 1984. Immediately Turkey began an investigation aimed at recovering the Hoard.The Museum policy, once again clear from the minutes, was not to help the Turkish investigation but to return the goods if ownership could be proven. Once it became clear that the pieces were stolen, the Museum began a rearguard action. The Museum claimed that the Turkish claim was too late. The Museum then attempted to share the hoard after admitting that it came from Turkey. Eventually the Museum returned the hoard in 1993. nearly 30 years after it was originally looted. Specific information on the Lydian Treasure items themselves is available on line. Click here. A piece by the journalist who exposed the hoard is also on the web. Click here.

Library Resources

Greenfield, S. 1996. The Return of Cultural Treasures. Cambridge, University Press.Renfrew, A.C. 2000. Loot, Legitimacy and Ownership. London, Duckworth.

Walker Tubb. K. 1995. Cultural Antiquities: Trade or Betrayed. London, Archetype Press.

See 'Editorial' in Antiquity for 1990 and 1995, and book reviews by Gill in Antiquity in June 1997 for a discussion of problems in the sales of cultural property by the major auction houses. Also look up Archaeology magazine (the magazine of the American institute of Archaeology which regularly has articles of stolen treasures. Also see Culture without Context below.