- Introduction

- Local Plans

- Archaeology and Planning

- PPG16 and the Nature of Archaeological Work

- The Current State of Archaeological Practice in England

- The Future of Planning Procedures in the UK

- Library Resources

Introduction

Most of the protection offered to archaeological sites is provided through the planning process, and the majority of field archaeologists working in Britain today will be doing work associated with planing applications.

Town and Country Planning (Assessment of Environmental Effects) Regulations 1988As a result of European legislation, in assessing planning applications for large developments an Environmental Impact Assessment must be made. This assesses the damage to the natural environment such as; areas of outstanding natural beauty, Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) and also archaeology ('material assets' and 'cultural heritage').

Town and Country Planning Act 1990Makes provision that all planning areas must have a local plan (by 1995), in which specific planning policies in the area are made explicit. Local plans state general planning policies for areas, as well as specifics about such things such as the exact geographical areas for which planning applications for housing will be considered. Planning applications must follow the guidance of the local plan.

Local Plans

These are very powerful pieces of planning law. They set out local policies on such matters as The environment, transport, the economy, retail, housing, community facilities, sport and recreation. They are map based, just like the local SMRs. Archaeology is included in the section dealing with the environment.

For Example: Chester objectives:- to preserve the archaeological resource through the planning process

- to retain the character of the historic landscape

- to ensure the adequate recording of archaeological sites which cannot be preserved

Maps list (i) Scheduled national monuments, or other nationally important sites, (ii) sites of regional or county importance, (iii) sites of district importance, (iv) sites of local importance (including stray finds).

Archaeology and Planning (Planning Policy Guidance note 16)

- Who is PPG16 for?

- The Structure of PPG16

- Key Points and Problems in PPG 16

- an overview of the planning process and PPG 16

In November 1990, the government published a guidance note for planning officers and all involved in the planning process called, Archaeology and Planning. Officially it is called Planning and Policy Guidance note 16, and more commonly PPG16). In Wales PPG16(W), is the same document but with different contact addresses in the appendices. There is also a slightly different structure to the planning guidance notes in Scotland, and archaeology is covered by two separate planning notes; but the same process is in operation.

The following sections present a summary of this document. A full version of PPG 16 Archaeology and Planning is available online. A synopsis of PPG 16 is available on the Current Archaeology website. Here, this also an introductory note about PPG 16 by Geoff Wainwright, who was Chief Archaeologist at English Heritage when PPG 16 was published, and who has often been considered to the the chief instigator of PPG 16.

Who is PPG16 for?

The introduction to PPG16 notes thhat this guidance note is intended for planning authorities, property owners, developers, archaeologists, amenity societies and the general public. In otherwords, all those people involved in the submission and asessment of planning applications.

The Structure of PPG16

There are two major sections in PPG 16 supplemented by a series of appendices. The first section (Section A) sets out the major reasons whhy it is important to consider the effects of development on the archaeological record. The second section (Section B) sets out the processes by which developers and planners can find out about archaeology, and how planning applications may be assessed in the light of the potential local archaeology.

Section A. The importance of archaeologyParag. 6.

Archaeological remains are a non-renewable

and fragile resource. Care must be taken to ensure that they are not

thoughtlessly destroyed. They are part of our national identity

Parag. 8.

Where nationally important remains are

affected, there should be a presumption in favour of their physical

preservation.

Parag. 14.

The key to the protection of most

archaeological (and historical) sites lies with local planning

authorities acting within the framework set out by central

government, in the capacities as planning, recreational and

educational authorities.

Section B. Advice on the handling of

archaeological matters in the planning process

Parag. 15.

Development plans should reconcile the need for development with the interests of conservation including archaeology. Detailed development plans (i.e. local plans and unitary development plans) should include policies for the protection, enhancement and preservation of sites of archaeological interest and of their settings. The proposals should define the areas and sites to which the policies and proposals apply. These policies will provide an important part of the framework for the consideration of individual proposals for development which affect archaeological remains and they will help guide developers preparing planning applications.

Parag. 16.

Archaeological sites of national importance will normally be marked in development plans. But....Authorities should bear in mind that not all nationally important remains meriting preservation will necessarily be scheduled; such remains and, in appropriate circumstances, other unscheduled remains of more local importance, may also be identified in development plans as particularly worthy of preservation.Sites and Monuments Records - SMRs

Parag. 17. Planing authorities should make use of their local SMRs

Planning ApplicationsParag. 18.

The desirability of preserving an

ancient monument and its setting is a material consideration in

determining planning applications whether the monument is scheduled

or not.

- The first step - early consultation between developers and planning authorities

- Field evaluations

- Consultations by planning authorities

- Arrangements for preservation by record including funding

Parag. 23. If planning applications are made without prior consultation, it is incumbent upon planning authorities to seek to assess the implications of the planning application upon any archaeological remains that may be affected.

Planning DecisionsParag. 27.

The case for the preservation of

archaeological remains must however be assessed on the individual

merits of each case, taking into account the archaeological policies

in detailed development plans, together with all other relevant

policies and material considerations, including the intrinsic

importance of the remains and weighing these against the need for the

proposed development.

Parag. 30. If planing authorities decide to preserve archaeological remains and also allow development to proceed, they must secure the preservation of the remains by means of a negative condition prohibiting the undertaking of development work until the archaeological remains have been taken care of.

Discovery of archaeological remains during developmentParag. 31. Ideally this should not happen. But if remains are found, and they are of national importance, English Heritage may have them scheduled, and then developers will have to seek Scheduled Monument Consent before any development work can proceed again. But voluntary discussion and compromise are desired.

Key Points and Problems in PPG 16

- PPG 16 makes a clear case for the protection of all archaeological remains on the grounds that they are both non-renewable, and that they are important for the creation of a sense of national and local identity.

- PPG 16 shifts the focus for the funding of rescue archaeology away from English Heritage, and towards developers, folllowing the 'polluter pays' principle.

- PPG 16 makes a distinction amongst archaeologists between curators (local government archaeologists (SMR officers, County Archaeologists) who monitor planning applications and the archaeological work associated with them, and contractors, who are archaeologists usually working in private archaeological companies who are employed by developers to survey, excavate, etc. a site in advance of or in response to a development proposal.

- There has been a huge debate about the quality of archaeological work that is done through PPG 16. This concerns the process of tendering for work at the lowest level possible to secure a contract, the rise of large national companies that possess little local knowledge, etc.

- How can one develop protection for landscapes and generate an understanding of the archaeological development of a particular period or area, if everything is about preserving the archaeological record, and decisions are taken at a very local level?

PPG16 and the Nature of Archaeological Work

PPG16 has brought about 2 primary forms of archaeological work: desk-based assessments and field evaluations. These are types of archaeological practice used by private archaeological contractors to determine the nature of the threat to the archaeological resource that will result fom a planned development. A desk-based assessment is the usual first course of action to determine this threat, followed by a field evaluation should the need arise. The definitions that follow come from the technical guidelines for archaeological work prepared by the Institute of Field Archaeologists.

Desk-Based Assessments

A desk-based assessment is a programme of assessment of the known or potential archaeological resource within a specified area on land, inter-tidal zone or underwater. It consists of a collation of existing written, graphic, photographic and electronic information in order to identify the likley character, extent, quality and worth of the known or potential archaeological resource in a local, regional, national or international context as appropriate. Desk-based assessments lead to:

- the formulation of a strategy to ensure the recording, preservation or management of the resource

- the formulation of a strategy for further investigation, whether or not intrusive, where the character and the value of the resource is not sufficiently defined to permit a mitigation strategy or other response to be devised

- the formulation of a proposal for further archaeological investigation within a programme of research

Field-Evaluations

A field evaluation is a limited programme of non-intrusive and/or intrusive fieldwork which determines the presence or absence of archaeological features, structures, deposits, artefacts or ecofacts within a specified area on land, inter-tidal zone or underwater. If such archaeological remains are present field evaluation determines their character, extent, quality and preservatin, and enables an assessment of their worth in a local, regional, national or international context as appropriate. Field evaluations usually lead to:

- the formulation of a strategy to ensure the recording, preservation or management of the resource

- the formulation of a strategy to initiate a threat to the archaeological resource

- the formulation of a proposal for further archaeological investigation within a programme of research

The Current State of Archaeological Practice in England

A Review of Assessment Procedures 1982-1991 (English Heritage 1995)In 1995 English Heritage published a review of the nature of planning assessments between 1982 - 1991. the review looked at the nature of the assessment required by local archaeologists, how that assessment was undertaken and the problems involved. Although the period involved predates the introduction of PPG16, in a number of areas (especially Hampshire and Berkshire) a system of assessment similar to PPG 16 was effectively being operated. This review therefore gives some clue as to the early problems of PPG 16. In the review English Heritage came up with the following findings.

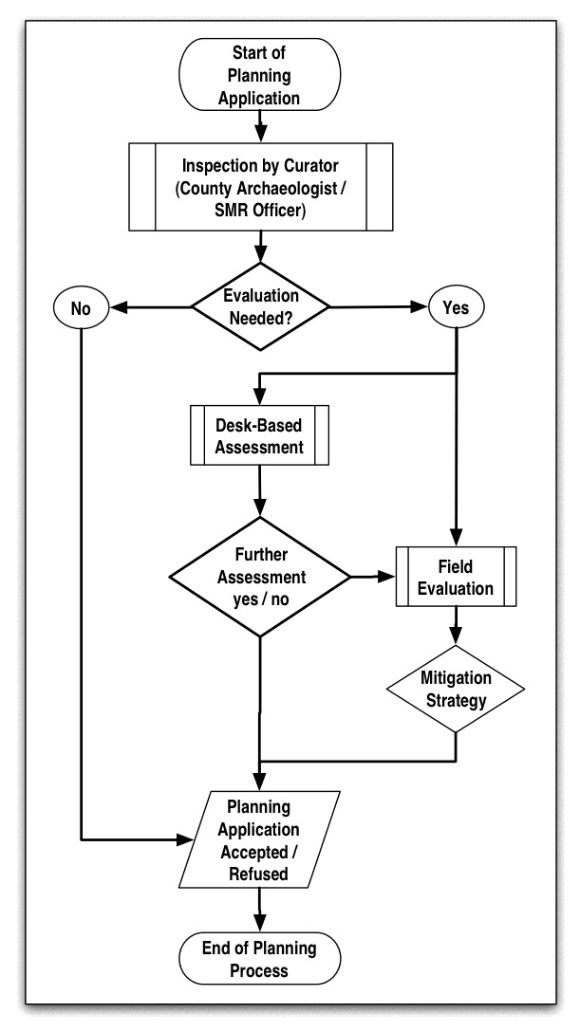

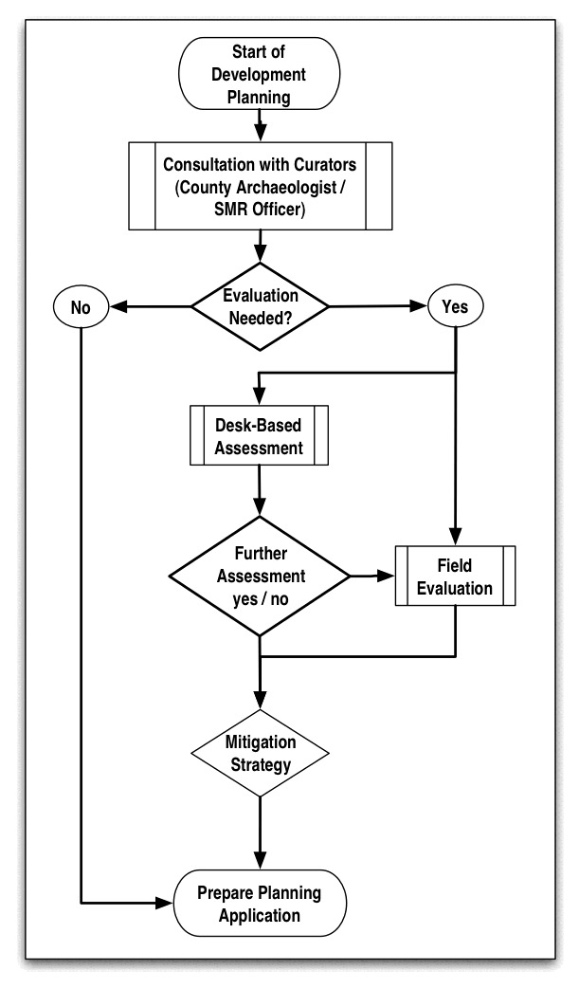

There is still some uncertainty about when an archaeological assessment should be made: either before the initial planning proposal is made or once the initial proposal has been made and it has been reviewed and referred. Both practices operate.

Both practices currently operate.

Archaeological Assessment Undertaken After the Submission of a Planning Application

Archaeological Evaluation Before the Formulation of a Planning Application

Ideally, curators and contract archaeologists would like to see archaeological evaluation happening before the formulation of a detailed planning application. If archaeological work happens in this order, developers see archaeologists lesss as people who are attempting to stop development proceeding and more as contractors helping to formulate a successful planning application.

The sample area of a site that is assessed is determined arbitrarily (usually 2%). Closer consideration needs to be given to quantitative and qualitative considerations. The application of trial trenching must be thought through more clearly. Trenches needed to be put where there was no prior evidence of archaeology, as much as where there was prior evidence.

There is no clear dissemination of the results of assessments. Copies of these reports are held by archaeological contractors, planning offices and developers. There needs to be a regional/national library(s) where all reports are lodged and notice of their existence needs to be made public - perhaps in British Archaeological Bibliography also SMRs and National Monuments Records office.

Sites and Monuments Records must be improved. they need to be more accurate and more accessible.

Archaeology after PPG16: archaeological investigations in England 1990-1999In 2002, English Heritage published their second review of archaeological assessments, after PPG16. the full report is available online, but a summary of the key discussion points indicates:

- investigations prompted by the planning process accounted for 89% of all archaeological work in England in the period 1990-99. Only 11% of archaeological fieldwork is purely research oriented;

- there were three times more investigations in 1999 than there were in 1990;

- the range of types of investigation also increased;

- there is little sign of bias towards a particular period or type of monument requiring assessment by curators;

- a perceived downside is that archaeologists cannot choose whhere to concentrate their fieldwork efforts. The locations are determined by planning aplications. It is possible, however, that this has meant that archaeologists are not able to return constantly to the same place (i.e. Wessex for early prehistory) and therefore fieldwork is being undertaken in less popular and potentially surprising regions;

- another downside is that quantity of archaeological feldwork is related to the number of planning applications. When there is a recession, the quantity of archaeological fieldwork will decrease accordingly;

- in general less than 1% of planning applications require / receive some form of archaeological investigation;

- for curators to be able to offer the best advice in response to planning applications, they require good records. there is a need to keep SMRs up to date and easily accessible. Restraint maps and planning strategy maps may be useful in helping curators. this is the purpose behind the Urban Achaeology Database project;

- the planning-archaeological relationship has created a number of archaeological companies (contractors) that can be loosely described as national in operation (Wessex Archaeology & the Oxford Archaeological Unit), regional in operation (e.g. Trent and Peak Archaeological Trust, Cotswold Archaeological Trust, and Thames Valley Archaeological services) and local contractors ( York Archaeological Trust, Suffolk Archaeological Unit).

The Future of Planning Procedures in the UK

There have been continual calls to 'streamline' the planning process so as to make the application for and the adjudication of planning permissions both cheaper and more speedy. Planning applications take time because those judgng the effects of the application now have quite a number of planning guidances to consider (of which PPG16 is but one of 20).

Prior to 1997 it was suggested that all planning guidance notes should be scrapped in favour of a single simpler document. Obviously archaeology would play a part, but a much smaller part, in such a document. Nothing came of these initial plans, but the proposal to reduce the number of planning guidance notes has arisen yet again in the light of demands from councils and developers to make it easier to develop in areas where development is needed such as urban regeneration areas. In 1998, the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions published a consultation document Modernising Planning to consider the simplification of the planning prosess. Most recently this has cropped up again in the context of the need to build many more houses in the south-east of England.

Library Resources

Darvill, T.C. and B. Russel, 2002.

Archaeology after PPG16: archaeological investigations in England

1990 - 1999. Research Report 10. Bournmouth University / English

Heritage.

English Heritage 1995. Planning for the

Past: a review of assessment procedures in England 1982-91.

London, English Heritage.

Link to the ALGY 399 Sydney Jones Library Reading List