Cecilia A. Western

Cecilia A. Western photographed by the author in 2004 at her private residence

What follows is an extract from a talk I gave at the Institute of Archaeology in the context of a research seminar titled "Kathleen Kenyon and women in heritage" organised by Dr. Karen Wright (on December 13, 2004 as part of the Autumn 2004 Research Seminar Series of the Institute of Archaeology under the theme of "Archival Memory - The Case of Palestine" - series organiser: Dr. Beverley Butler). My main aim with this talk was to pay a long overdue tribute to Cecilia A. Western, one of the pioneer figures in the field of charcoal macro-remain studies.

Notes on a personal debt ...

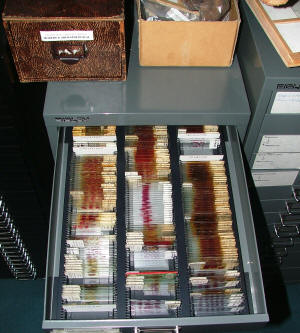

Cecilia A. Western is the reason why the Institute of Archaeology has one of the best and most complete archaeobotanical collections in the UK, including (besides seeds) wood, charcoal, archaeological specimens of wood, and pressed herbarium specimens. She donated (at the instigation of Gordon Hillman) her collection to the Institute of Archaeology in 1984.

Thirteen years later, in 1997, I arrived at the Institute of Archaeology from Sheffield University where I had just completed a masters degree on environmental archaeology, to start my doctoral research working on wood charcoal macro-remains from Çatalhöyük. Needless to say that the principal reason why I could do this at the Institute of Archaeology was the presence here of her reference collection. Or, to be more precise, the scatter of it in drawers, cupboards and folders lying around in the then Palaeoecology laboratory. Fortunately, nowadays this is no longer the case. Her collection has been properly catalogued and housed, while plans are now in hand for its reproduction in digital form so that it can become as widely available as possible for the benefit of all researchers.

My sense of intellectual debt to her is therefore quite obvious. Yet, other than the existence of her collection at the Institute, not many people even in this building are aware of her history and her contribution not only to the Institute of Archaeology, but to the field of archaeological science in general ...

A short biography

Cecilia A. Western was born in 1917. She received her first training in horticulture and garden design at the Horticultural College in Warwickshire. Between 1936-38 she trained for the Royal Horticultural Society Diploma. The 2nd World War however disrupted any career plans she had at the time. For its duration she served in the anti-aircraft defences and more specifically in radar maintenance.

After the war was over, she took on her first appointment at the Manchester Museum as an assistant researcher, working for the conservation on the Petrie Egyptological collection. This was also her first acquaintance with archaeology. I remember that when I asked her how she got on this task without any previous training, she replied that at those times the only training you got was practical one.

Yet she did embark on a more academic road soon afterwards and in 1950 she got her degree in History from Birkbeck College. A little later she worked for a short period at the Institute of Archaeology at the time when Vere Gordon Childe was director, as assistant to Ioni Gedye, the then head of the Conservation department.

The real turning point came however in 1953 when she first worked at Jericho with Dame Kathleen Kenyon as a conservator in the field. She recalls Jericho and Kenyon’s team as her best and most memorable field experience. This was also the time when she started developing an active interest in wood identification and the collection of reference material. Cecilia Western had taught herself wood anatomy with the aid of the only manuals available at the time: the Forest Products Research Handbooks of HMSO. Part of her on-site work had to do with the conservation of furniture items and artefacts from the Bronze Age rock cut tombs. Yet her initial attempts were not crowned with success: She described to me how her efforts to identify the woods used as raw materials failed at the beginning, because there was no anatomical structure preserved and the wooden items themselves were very friable. So she opted instead for embedding them in paraffin wax, in order to maintain at least their shape.

In 1955 she decided to take a year out travelling. She and her companions followed the beaten track of British travellers across southern Europe. Having entered Greece via Belgrade and Skopje, they travelled as far south as Sparta and the medieval castle-city of Mystras, and also paid a visit to Mycenae. Their trip took them through Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. From Pakistan they entered India and travelled southwards through Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka to Madurai in the southernmost state of Tamil Nadu. It is perhaps a thought-provoking coincidence that these were the exact same areas where I travelled in India more than 50 years later, collecting wood specimens for my ecological and wood anatomical study of South Indian trees and shrubs. Finally, from Colombo she embarked on a boat trip to Australia. She describes this trip as one of the most memorable experiences of her life, if only because it encapsulated a moment in time when such endeavours were still feasible. Soon afterwards the Middle East was no more what it used to be ...

With her return to England in 1956 she entered the Forestry Institute at Oxford. Like many specialists to this day (I, as a research fellow, have been no exception) she used all her annual leave in order to participate in archaeological field projects, and these were always abroad. Other than Jericho, she has worked in excavations in south Italy run by the British School in Rome and in Libya with Dame Kathleen Kenyon. She also spent three seasons digging in Jerusalem, and worked in Jordan (Petra) and Syria. She furthermore acted as a wood specialist for a number of projects all over the Eastern Mediterranean. She worked with Diana Kirkbride in Beidha in 1966 and 1967 and had just managed to get out of the region when the Six Days War broke out. In 1969 she visited Israel on a travel grant from London University and collected wood specimens in Eilat and Bersheeva. This was also the year when she graduated from Oxford’s St Hughe’s College, having completed her thesis on the ecological interpretation of ancient wood charcoals from Jericho at the Forestry Institute. With the active encouragement of Kenyon, who recognised the importance of the charcoal project, she had amassed a large collection of charcoals from stratified archaeological deposits, which became the object of her analysis. Hers was the first dissertation done on the analysis of wood charcoal macro-remains from an archaeological site, and was even more important for including the first identification key devised specifically for archaeological carbonised plant material. After 1969 she took on a conservation job at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, being responsible for the curation of organic materials, which she kept on until her retirement.

Legacies awaiting recognition ...

If I am to summarise in a few phrases what I consider as the greatest legacy of Cecilia A. Western, other than her reference collection of course, I must say that her work contributed to opening the road for wood and particularly charcoal macro-remain studies to become a truly integrated part of bioarchaeological science and specialist fieldwork. She belonged to a pioneer generation of archaeological science specialists who chose (when circumstances permitted) to work in the field instead of being confined in their laboratories. She also developed methodologies and analytical approaches that were suitable for and tailored to the requirements of archaeological reasoning and interpretation. Her work is still quoted in the literature more than forty years after it was first published. Her scientific papers were on my reading lists when I started my doctoral research, and I always recommend them to my students as examples of genuinely innovative, archaeologically meaningful and well-written research. Her professional achievements can thus be considered as really outstanding.

The title page of C. Western's article publication on the interpretation of archaeological charcoal macro-remains from Jericho (Western, C. A. 1971. The ecological interpretation of ancient charcoals from Jericho. Levant 3: 31-40).

Dame Kathleen Kenyon is perhaps best known as the person who established Near Eastern Neolithic archaeology as a distinct field and produced its basic culture-historical outline. Her meticulous excavations and recording strategies together with the work of Dorothy Garrod on Natufian sites and, later, that of Diane Kirkbride with the horizontal exposure of the Neolithic village of Beidha, created a solid foundation for later generations of archaeologists and prehistorians working in the Southern Levant. Yet, at the same time, Kenyon is perhaps least known for being one of the first field project directors (likely the first altogether) who employed and brought on-site a diverse lot of archaeological science specialists to work on materials ranging from human and animal bone to seeds, charcoal, wood, conservation, various types of chemical analyses, etc. She also followed closely the career paths of her associates and took a personal interest in their professional development and work future. I have so far failed to locate any references relating to the impact of this aspect of her research practices and strategies, or the comments it might have elicited from other (academic and professional) quarters at the time. Still, it remains the case that (to this day) very few projects have such a diversity of analytical and specialist expertise directly associated with them. It follows that her contribution to the development of what we call today "archaeological science" (in the broadest possible sense of the term) and its integration with mainstream fieldwork and analysis, should not go unnoticed or understated. It certainly deserves wider recognition.

© Eleni Asouti, 2006